The California Art Club: A History (1909-1995)

by Susan Landauer, Ph.D.

From American Art Review, March 1996, p.144-151

Founded in Los Angeles in 1909 and currently headquartered in Pasadena, the California Art Club is one of the oldest and largest art associations west of the Mississippi.(1) In its formative years, the club was closely tied to Southern California’s leading Impressionists. Well-known names such as Franz Bischoff, Carl Oscar Borg, Maurice Braun, Benjamin Brown, Alson Clark, Frank Cuprien, Anna Hills, Edgar Payne, Hanson Puthuff, William Ritschel, Guy Rose, Donna Schuster, Jack Wilkinson Smith and William Wendt are found on the early club rosters. Recent museum exhibitions and publications have begun to reinstate the reputations of these plein-air painters, suggesting a fresh look at the institution they created, the California Art Club.(2)

Edgar Payne, The Gorge

Oil on board, 28″ x 24″

Courtesy of George Stern Fine Arts

As an outgrowth of the Painter’s Club, an informal sketch and critique group formed in 1906, the California Art Club quickly became the largest and most prestigious art association in Southern California.(3) The club owed much of its success to an expansive membership policy.

Franz Bischoff, Untitled (Still Life, Roses)

Oil on canvas, 32″ x 20″

Courtesy of Joan Irvine Smith Fine Arts

While the Painter’s Club had excluded women, females were welcomed in the California Art Club from the outset. Sculptors were also invited to join, though the organization and its exhibitions were dominated by painters. And despite the name, California residence was not a requirement for membership, even though there were certainly no scarcities of artists in the state. Indeed, the club was chartered during a swell of artistic migration to Southern California. Perpetual sunshine and favorable year-round painting conditions established the region as an artist’s mecca.

California Art Club members joined the legions descending on their state to find their fortunes. Their migration coincided with the completion of the transcontinental railroads, the Panama Canal, and the phenomenal series of land booms that followed. Artistic renditions of California’s scenic beauty aided developers luring new businesses and settlers into the region.

Regardless of prior thematic and stylistic predilections, California Art Club members were profoundly affected by their surrounding landscape. They painted in plein-air, encouraged by the mild climate, capturing the singular quality of Southern California light.(4) Their painting fit comfortably within the Impressionist style, with its emphasis on color and light, broken brushwork, and its spontaneous apprehension of nature. Many of the artists developed a distinctive approach, seeking, as did Maurice Braun, expressions unique to America.(5) Their resulting styles ranged from the blocky brushstrokes of William Wendt to Elmer Wachtel’s otherwordly tints.

Mabel Alvarez, Arabella

Oil on canvas

Courtesy of George Stern Fine Arts

Elmer Wachtel, Untitled Landscape

Oil on canvas, 20″ x 26″

The Fieldstone Collection

Easy accessibility of their canvases won these artists a large audience. Early California Art Club members exhibited widely in Los Angeles and San Francisco(6) and in the commercial galleries of Southern California. A ready market enabled many artists to acquire posh studio-homes, some quite excessive.

William Ritschel’s marine paintings sold so well that he built his “Castle” in the Carmel Highlands. Based on a fifteenth-century Basque design, Ritschel’s fortress-like home afforded spectacular views of the Pacific Ocean. And Franz Bischoff built an extravagant Italian Renaissance-style mansion on the banks of Pasadena’s Arroyo Seco. Equipped with its own art gallery for public exhibitions, Bischoff’s house had skylit cathedral ceilings and oak floors covered with Turkish rugs and polar bear skins.

Unlike their East Coast counterparts, California Impressionists achieved immediate recognition. Their road to critical acceptance was well paved. By the 1910’s, East-coast Impressionism was the entrenched establishment; as E.P. Richardson observed, a “kind of academy.” The West Coast movement enjoyed the support of a boosterish press from the outset, and was encouraged by real estate marketers. It never experienced the abusive or indifferent reception of early Impressionists. California’s enthusiasm for this art was expressed by the near-apotheosis of Childe Hassam and William Merritt Chase at 1915’s Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. In this sense, California Impressionism was never actually avant-garde.

Donna Norine Schuster, In the Garden, 1917

Oil on canvas, 30″ x 30″

Fleischer Museum

The California Impressionists success, however, reflected more than regional taste for regional art; many California Art Club members traveled between Los Angeles and Chicago, New York, and various European cities, represented in both national and international galleries. The consumption of eucalyptus-framed California landscapes in European and Eastern art markets reflected an appetite for the exotic, even if rather domesticated.

In Los Angeles, however, the art club’s high profile personified Southern California’s own search for identity. Journals and newspapers lionized art club activities as hopeful evidence of the region’s rising cultural sophistication. Everett C. Maxwell, assessing the club’s activities for the Fine Arts Journal in 1913, mixed tropes of Renaissance progress, millenarianism, and Western mythology:

“From a dozen different writers upon subjects pertaining to the development and trend of art in the west, the word has gone forth to the world that California, that land of golden light and purple shadows, is destined in the course of the next few years to give us a new school of landscape painting…Conditions seem right for a renaissance of art in California…If this art epoch of golden prophecy does not come to pass, it will not be the fault of the California Art Club.”(7)

Hanson Puthuff, Flame of Sunset

Oil on canvas, 30″ x 32″

Courtesy of William A. Karges Fine Art

Maurice Braun, California Hills

Oil on canvas, 40″ x 50″

The Irvine Museum

Los Angeles Times critic Antony Anderson evoked his own priestly imagery, referring to a club’s campaign to “enlighten” the “laity.”(8) Anderson recollected the parable of Mohammed and the mountain, describing the exhibition and lecture circuit the club slated to travel throughout the state and beyond. As the tour’s featured lecturer, Alma May Cook expressed the club’s hope to raise California’s consciousness as well as its hyperbolic ambitions for the West Coast:

“It is a conceded fact that the West is to be the art center of the future, and surely California, with its vast storehouse of everything that is beautiful [and] appeals to the very soul of the artist, will take the lead…(9)

Guy Rose, Mist over Point Lobos

Oil on canvas, 28 1/2″ x 24″

Fleischer Museum

From the club’s very inception, Anderson’s regular columns in the Los Angeles Times epitomized the provincial mentality of the local press. Anderson, an early club member, seldom tempered his effusive praise. Perhaps most significant was his romantic casting of the club as an avant-garde. In a November, 1911 review appearing in the Los Angeles Times, Anderson wrote that he found the group’s exhibition “both a revelation and a revolution.” It was not, Anderson explained, a manifesto on modernism with a well-defined campaign, but rather, a broad experimentalism.

Guy Rose, The Blue Kimono, 1909

Oil on canvas, 31″ x 19″

Courtesy of Paula and Terry Trotter

“No man, however he may see fit to express himself in paint, may be considered a heretic in the California Art Club any longer. He may cross-hatch with a pin or plaster the paint with a broom. He may be enamored of infinite detail or he may woo the robust muse of impressionism. He will not be thrown out of the club because of any particular predilection. In short he may paint as the spirit moves him…”(10)

In reality, the club’s basic conservative bent overshadowed any attempts to establish modernist credentials. Well into the 1930’s, and aware of Europe’s evolving modernisms, the bulk of its membership continued to paint traditional landscapes. As early as 1915, just two years after New York’s Armory Show introduced Europe’s avant-garde to the East, Anderson reported the club’s exclusion of recent European movements. Reviewing their sixth annual exhibition in Exposition Park, he noted: “The paintings are of all schools, including the modern French and modern American, with a slight tendency to post-impressionism. The cubists, futurists and other ‘ists’ are not included.”(11)

Effects of modernism in American art reverberated across the country following the Armory Show, but did not penetrate the club until after 1919. That year, Anderson reported a schism threatening to split the art club’s ranks in an article subtitled “A Fly in the Ointment.”(12) Helena Dunlap, an eight-year club veteran, with like-minded artists including Henrietta Shore and Edouard Vysekal, formed a splinter organization called the California Progressive Group devoted to the fostering of modern art.(13)

According to Anderson’s account, the new group, espousing total freedom of rules relating to style and technique, scheduled to meet the trustees of the Museum of History, Science, and Art and demanded annual exhibition space alongside the California Art Club. The situation culminated in a confrontation between Dunlap’s group and a protest committee from the art club at the museum. Impending chaos was narrowly averted when the museum granted exhibition inclusion of the California Progessive Group.

This episode underlines the art club’s highly institutionalized authority in Southern California. By the late teens. the region had spawned dozens of specialty clubs, devoted to everything from miniature painting to printmaking. But proliferation of these organizations did not diminish the growth and prestige of the California Art Club. By embracing painting, sculpture, the allied arts, and women artists, and because of its open-door policy regarding other art associations, the club’s domination continued.

Despite this success, the California Art Club lacked a permanent clubhouse; in the mid-1920’s, this became a primary goal of club members. The day after Christmas in 1926, the Los Angeles Times reported that the club’s wish had been fulfilled beyond its wildest expectations.(14) Wealthy socialite Aline Barnsdall, daughter of the oil tycoon Theodore Barnsdall, donated her estate to the California Art Club for the next fifteen years.

Frank Cuprien, Golden Sunset

Oil on canvas, 13 1/2″ x 17 1/2″

The Fieldstone Collection

William Wendt, Home of the Quail, 1928

24″ x 32″

Fleischer Museum

In the fall of 1927, the club moved into its opulent new quarters, the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Hollyhock House on eight acres overlooking Hollywood. Surrounded by gardens and olive groves, the new clubhouse came complete with lavish furnishings custom-designed by Wright, a rare collection of Asian art, multiple galleries for exhibitions, a concert hall, and an outdoor theater.

The Hollyhock House ushered in a new era of glamour and prosperity for the California Art Club; it became a premier cultural center of Los Angeles. The club instituted “salon dinners” featuring celebrities and international heads of state, as well as a lecture series on art, literature, music, architecture, theater, and film. Keynote guests at these events included Princess Der Ling of China, who spoke of Chinese porcelain, Henry MacMahon of Cecil B. DeMille Studio, who gave a talk on “Art and Motion Pictures,” and Stanton MacDonald Wright, lecturing on the contemporary fusion of Asian and Occidental art.

Throughout the year, outdoor performances packed the theater, and Los Angeles high society was engaged by black-tie banquets and masquerade balls. The club’s exhibition schedule accelerated to two shows per month, and its programs were expanded to include annual exhibitions of architecture and allied arts with symposia featuring such eminences as Richard Neutra, Henry Greene, and Frank Lloyd Wright. Loan exhibitions were also shown at the Hollyhock House. In 1928 alone, it displayed works by Matisse, Derain, Diego Rivera, Rockwell Kent, Arthur B. Davies, and Edward Hopper.(15)

Much of this activity ended with the 1929 stock crash. In June of 1930, a letter from Julian Garnsey, president of the club, grimly reported: “Our numbers are steadily declining. We have lost eighteen members by resignation since January 1st, 1929, and ten by death…”(16)

The California Art Club remained in the Hollyhock House, but its programming and membership steadily dwindled. With the onset of World War II and a rising tide of international modernism, plein-air painters who founded and gave the club status were all but forgotten; the California Art Club disappeared from the public eye.

Anna Althea Hills, Old Ranch

Oil on canvas, 24″ x 20″

Fleischer Museum

Jack Wilkinson Smith, Seascape with Rocks, c. 1925

28 1/4″ x 34 1/2″

The Jonathan Club

Carl Oscar Borg, California Landscape

Oil on canvas, 36″ x 43″

The Fieldstone Collection

However, the recent revival of traditional plein-air painting, spear-headed by organizations like Santa Barbara’s preservation-oriented Oak Group and the Plein Air Painters of America, has resurrected the California Art Club.(17) In its current incarnation, the club claims a membership of more than 500 artists throughout the country. Under the leadership of Peter Adams, president since 1993, the club has organized several museum exhibitions and reinstituted large annual shows at the Los Angeles Arboretum. In 1994, the 85th Annual Gold Medal Exhibition was the club’s largest show in decadesm with over 250 works of art by artists such as Meredith Abbott, Denise Burns, John Comer, Karl Dempwolf, and Ron Elstad. This new generation works en plein-air, in a range of styles from realism to Impressionism, inspired by the same love of nature that touched their predecessors.

Peter Adams, Morning Light through the Eucalyptus Forest

Oil on canvas, 18″ x 24″

Courtesy of the California Heritage Gallery, The Craftsman’s Guild

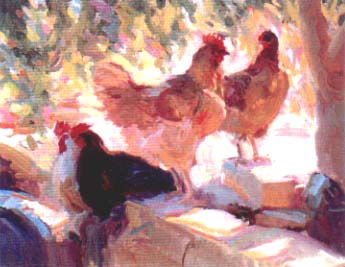

Denise Burns, Junkyard Chickens, 1993

Oil on canvas, 24″ x 30″

Courtesy of the California Heritage Gallery, The Craftsman’s Guild

(1) The author would like to thank Nancy Moure for generously sharing her extensive archive on the history of the California Art Club. Moure has recently deposited copies of these papers in the club’s archives in Pasadena. For more on the California Art Club, see Moure’s essay on the club in the Irvine Museum’s forthcoming publication, Impressions of California (in conjunction with the PBS series of the same title, produced by KOCE, Orange County), scheduled for September, 1996.

(2) The revival of interest in California Impressionism dates back to Nancy Moure’s pioneering efforts in the 1970’s. Her exhibition, Los Angeles Painters of the Nineteen-Twenties, at California’s Pomona College, was the first evaluation of these artists in decades. Other museum exhibitions since then have included the Laguna Art Museum’s Southern California Artists: 1890-1940 (1979); the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s Painting and Sculpture in Los Angeles, 1900-1945 (1979); and Early Artists in Laguna Beach: The Impressionists (1986) and California Light: 1900-1930 (1990), both at the Laguna Art Museum.

(3) See “The Painter’s Club,” Los Angeles Times, March 25, 1906; and Antony Anderson’s column, “Art and Artists,” in the Los Angeles Times, February 17, 1907; April 7, 1907; January 6, 1907; October 11, 1908; October 18, 1908; November 7, 1909. Anderson reports the Painter’s Club disbanding and the chartering of the California Art Club in his December 12, 1909 column.

(4) See Patricia Trenton and William H. Gerdts, California Light 1900-1930 (Laguna Beach and San Francisco: Laguna Art Museum in association with Bedford Arts, 1990).

(5) Telephone interview with Maurice Braun’s daughter, Charlotte Braun White, December 13, 1995.

(6) Beginning in 1914, the club held twenty-five annual exhibitions at the Los Angeles County Museum of History, Science, and Art in Exposition Park; some of these traveled to San Francisco Art Association galleries.

(7) Everett C. Maxwell, “Exhibition California Art Club,” Fine Arts Journal 28 (January-June 1913), 189-90.

(8) Los Angeles Times, October 3, 1915.

(9) Ibid.

(10) Antony Anderson, “Art and Artists,” Los Angeles Times, November 26, 1911.

(11) Antony Anderson, “Artists’ Best Work on View,” Los Angeles Times, October 5, 1915

(12) Antony Anderson, “Of Art and Artists,” Los Angeles Times, August 31, 1919; see also, “Of Art and Artists,” Los Angeles Times, September 7, 1919.

(13) This association seems to have been an outgrowth of the Modern Art Society, established in 1916 by Dunlap, Shore, and others.

(14) “Art Club Gains Long-desired Home,” Los Angeles Times, December 26, 1926. The city of Los Angeles was granted joint use, during this period, for recreational purposes. See “Art Club Takes Over New Home,” Los Angeles Times, September 1, 1927; Francis William Vreeland, “A New Art Centre for the Pacific Coast,” Arts and Decoration 28 (November-April 1927-28), 64-65; Francis William Vreeland, “The California Art Club’s New Home,” American Magazine of Art 18 (January, 1927), 312-14.

(15) The California Art Club Bulletin 8 (August 1928), n.p.

(16) Julian E. Garnsey, “President’s Letter,” The California Art Club Bulletin (June, 1930), n.p.

(17) See Pam Ludwig, “The Revival of the California Art Club,” Southwest Art (February 1995), 93-100.